Sustainability is a concept that has been abused to the point where it is almost meaningless – it is widely used to refer merely to practices that claim to be more environmentally sound than others. Even those who understand its real meaning have begun to use other buzzwords like resilience or even anti-fragility to describe what they mean.

“Disingenuous” is another big word, one that is used much less, but I think neatly describes much of the abuse that the word “sustainability” has endured. Wiktionary defines this as “assuming a pose of naivete to make a point or for deception.” It seems to me that people on both sides of the sustainability debate are guilty of this (especially the “for deception” part), to the great detriment of a discussion that is of critical importance today. There is much to say about this, but it would probably be best to start by saying what I think sustainability is really about, frankly and without any “disingenuousness”.

Wikipedia says, “Sustainability is the capacity to endure. In ecology the word describes how biological systems remain diverse and productive over time. Long-lived and healthy wetlands and forests are examples of sustainable biological systems. For humans, sustainability is the potential for long-term maintenance of well being, which has environmental, economic, and social dimensions.”

The Wikipedia article goes on at some length but only touches briefly on what is, for me, the core of the issue. And that is that, for humans, the capacity to endure is in serious doubt. It is this concern that makes sustainability an important issue. As much as we might like to believe otherwise, we are completely dependent on the living environment of this planet for air, water, food and much else that we need to survive. There are, quite simply, limits to how many humans this planet can support.

The fact is that we have already exceeded the carrying capacity of this planet. How is this possible? Well, the term “carrying capacity” refers to the population that can be supported sustainably, that is, on a long term basis without causing degradation to the environment. We are managing to exceed this limit by borrowing from the past (using fossil fuels) and the future (overexploiting aquifers, forests, fisheries, topsoils and so forth). We are depleting these resources and using them in such a way that the byproducts pollute the environment. All this reduces the carrying capacity of the planet and at the same time our population continues to grow.

Other species in this sort of situation experience a population collapse, a dieback. This continues until what is left of the environment can support what is left of the population.

So, are we headed towards some sort of a crash – a dieback of the human population? Will we take a great many other species along with us, due to the way we are destroying their habitats and ours? To me it seems a certainty, if we do not make some changes in the way we are currently living to drastically reduce the burden we are placing on the environment.

Many people, when faced with this reality, fall back on the idea that our ability to anticipate and solve problems will see us through. And I agree, but in this case the solution is going to be a broad cultural change, not the painless application of higher technology that most would expect. And there is also a good chance that inertia, denial and short term thinking will prevent us from responding in time, with disastrous results. Reality will likely be somewhere between the best and worst possibilities, but the sooner we get going, that better our chances are.

So, if you are wondering what the big deal is about sustainability, that’s it, and it should be enough to make anyone stop and think.

Please note that I am not talking about some sort of apocalypse. But a slow degradation of conditions on a timescale of years and decades seems inevitable. Global warming is already starting to undo the ideal conditions that our agriculture depends on. A few more years of drought like the one we experienced in North America in 2012 and we will find ourselves genuinely unable to feed everyone. Since our capitalist system is set up to administer “rationing by price”, the poor will feel this first and hardest.

The size of the burden we place on the environment is determined by the size of our population, the level of material affluence we enjoy, and amount of waste involved in attaining that level of affluence. This is the classic consumption equation, I = P × A × T, where: I = Environmental impact, P = Population, A = Affluence, T = Technology (what I refer to as level of waste, or efficiency). Each of the terms in that equation warrant a little further examination.

Population: There are currently over 7 billion people on this planet, with 9 billion expected by the middle of this century. The most reasonable estimates I have been able to find point to one or two billion as a sustainable level of population. Other things being equal, it is a straightforward conclusion that a reduction in population would reduce the stress on our environment. But things are not equal, because the other two terms of the equation vary greatly across the human population.

Technology: we have such a love affair with technology these days that it is easy to jump to the conclusion that technology must have a value less than 1 in the equation, thus reducing our impact on the environment, such that an advance in technology would enabling us to enjoy our current level of affluence while using less in the way of energy and material resources and creating less pollution. For many of the poor in the world this is true – a little more access to technology, just some better tools and techniques, really, could greatly improve their lives with little additional impact on the environment. When the rich adopt new technologies, though, it often actually leads us to higher levels of consumption and/or pollution.

.Affluence: specifically, material affluence, the amount of resources each of us consumes and the amount of pollution we create in the process. It is important to note here that once the basic necessities of life are provided, additional material consumption and “quality of life” are not strongly linked. Consumption increased dramatically in North America over the last century, while quality of life actually decreased for many people. It you are or have ever been “stuck in the rat race”, you’ll know what I mean.

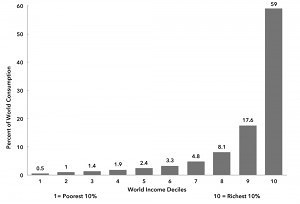

Source: World Bank, 2008 World Development Index, 4, http://data.worldbank.org.

It is a bit little hard to see the numbers in the graph above, but what it is really about is the great discrepancy that currently exists between rich and poor. Specifically, it shows us is that the poorest decile (10%) only consumes half a percent of the total and poorest 20% only consume 1.5%, a small fraction of an even share, which would be 10%. While the richest decile of humans account for 59% of consumption and the richest 20% account for a whopping 76.6%. This means that the richest 10% out-consume the poorest by a factor of almost 120! So it’s pretty clear that the poor are not to blame for our overall overconsumption, and controlling their population isn’t the real issue. The real issue is bizarre levels of overconsumption by the rich.

It is interesting to engage in a moment of daydreaming about what the effect of reducing that overconsumption might be. If that richest 20% of our population was to reduce its consumption down to an even share (20%), our overall consumption would be reduced to less than half of its present level. And in the process no one would be denied the necessities of life, in fact those in the top 20 percent would still consume more than the rest of the population, just not by so wide a margin.

I am not suggesting that this is exactly what we should do, and it would by no means completely solve our problems, but it would give us breathing room to begin seriously doing something about them. Like getting our population under control by educating women and making family planning alternatives available to them. Like reducing the burden on the areas of the environment we have not yet seriously damaged, and allowing those areas that are seriously damaged a chance to recover.

Of course I do realize that the richest 20% are also overwhelmingly the people who run the world. For the most part they run it for their own short term benefit, so nothing of this sort is likely to happen any time soon.

This where the word “disingenuous” comes into the discussion. If you listen carefully to discussions of sustainability by the overconsuming rich (and most people in the US and Canada fall into that category) you will hear a lot of deception disguised as naivete. Sadly it is to be found on both sides of the argument. Let me explain what I mean.

On one side of the discussion are the “Business as Usual” people, who have a great deal invested in the way the world currently works, and want to see it continue that way. Here is a link to a pretty good statement of their viewpoint: only growth can sustain us. I am pretty sure that these people realize that we live on a finite planet and that there are some pretty clear limits which are already bringing an end to unbridled growth. But they simply cannot conceive of any alternative to an economy based on growth. How they reconcile the conflict is quite simple: as long as more and more people consume less, a few can continue to consume more. The people at the top of the heap earned their position there and they deserve their privileges. (NOT!) This may even represent a real solution to our sustainability problem, albeit a repugnant and immoral one from my viewpoint.

The majority of people in political positions of power hold this viewpoint and they know they can stay in power by convincing the public that everything is OK and that with just a little tweaking the system can be switched back into growth mode again and everything will return to normal. And of course they are the ones with the expertise to do that tweaking. One even hears these people spouting bogus ideas like “sustainable growth” and “being rich enough to afford to fix the environment”.

This sort of playing dumb to sell a position beneficial to your own interests is what I would call really disingenuous. It is compounded when powerful organizations (usually corporations with a vested interest) spend money to set up fake think tanks or supposedly “academic” institutes which then proceed to produce misinformation/pseudoscience about peak oil, global warming and so forth.

On the other side of the discussion are the people we might as well call the “greens” (small “g”). They are quite aware of the sustainability challenges we face. They also believe (as I do) that the place to start reducing our burden on the environment would not be among the poor, but among the rich who consume so much that their lives are actually burdened by that consumption. But they are equally aware that being less rich is a pretty tough idea to sell. So they have a conflict to resolve as well. It is a serious one because, for the purposes of this discussion, the great majority of people in a places like the US and Canada qualify as rich.

The greens resolve this issue this with the “soft sell”, trying to make sustainability a “cool idea” and fun to take part in. Perhaps the clearest example of this is the Transition Town movement. Their leaders are clearly aware of the seriousness of the challenge we face and the degree of change in our lifestyles that is going to be necessary. But they speak of a process which is “more like a party than a protest march”. In fairness, I believe that is a reference to the camaraderie experienced by those by those working together in this cause, but I have also observed that many of people who are attracted to the Transition movement are not fully aware of the situation, and would not be so enthusiastic if they knew where the movement was really leading them.

And, not just to pick on Transition alone, there are many other groups selling ideas like saving polar bears, investing in renewable energy or buying “carbon credits” as the answer to the problem – answers that won’t require any significant change in our lifestyle.

I guess by this point it should be clear that, once again, I see this sort of thing as really disingenuous. It is vital, in my opinion, that we come to grips with the reality of the problem facing us and having done so, get to work fixing it. There is a solution, it’s just that the people who are causing the problem (and have the power to solve it) have all agreed not to discuss it. Until this changes, things will only get worse.

Here are some links to further discussions of sustainability: